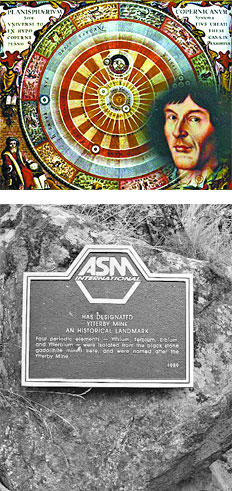

NICOLAS COPERNICO

PLACA CONMEMORATIVA DE YTTERBI, LUGAR QUE DA NOMBRE A CUATRO ELEMENTOS

En noviembre de 2011, la tabla periódica de los elementos le dio la bienvenida oficial a tres nuevos elementos químicos: el darmstadtio (Ds 110), el roentgenio (Rg 111) y el copernicio (Cn 112).

La elección de estos nombres y símbolos es el resultado de muchas discusiones y negociaciones entre miembros e instituciones de la comunidad científica.

Por Claudio H. Sánchez

El nombre de un elemento químico perpetúa a un lugar (en el primer caso a Darmstadt, en Alemania) o a una persona ilustre (en los otros dos casos, a Roentgen y a Copérnico) y cada uno defiende a sus favoritos.

En los años ’60, durante la Guerra Fría, se planteó este problema con algunos elementos descubiertos independientemente por laboratorios de Estados Unidos y de la Unión Soviética.

En particular, el elemento número 104 fue obtenido en 1964 en el Instituto de Investigación Nuclear de Dubna, en Rusia.

Lo llamaron dubnio y luego kurchatovio, en honor a Igor Kurchatov, considerado padre de la bomba atómica soviética.

En 1969 fue redescubierto por investigadores de la Universidad de Berkeley y propusieron el nombre rutherfordio, por el físico neocelandés Ernest Rutherford.

La Iupac (Unión Internacional de Química Pura y Aplicada) adoptó temporalmente el nombre unnilquadium (uno-cero-cuatro), siguiendo un criterio sistemático para designar elementos a partir de su número atómico.

Finalmente, en 1997, se aceptó oficialmente el nombre rutherfordio (Rf).

El nombre dubnio se aplicó al elemento 105.

EN LA TIERRA COMO EN EL CIELO

Muchos elementos químicos han sido bautizados con el nombre de países, ciudades o distintas regiones de la Tierra.

A veces, por la patria de su descubridor, como es el caso del polonio (Po), descubierto por María Sklodowska, madame Curie.

Otras veces, por su lugar de procedencia, como el cobre (kyprus), abundante en la isla de Chipre.

Y nuestro país es un ejemplo del caso contrario: ha sido bautizado con el nombre de un elemento, la plata.

Algunos países, ciudades y regiones tienen el privilegio de haber inspirado el nombre de más de un elemento.

Por ejemplo, Francia tiene al francio (Fr) y al galio (Ga), aunque también se cree que este nombre es un autohomenaje que se hizo su descubridor,

Paul Emile Lecoq de Boisbaudran: le coq, en francés, quiere decir “el gallo”. California tiene al californio (Cf) y al berkelio (Bk), por una de sus universidades más famosas.

En este sentido, el caso más notable es el de Ytterby, un pequeño pueblo minero ubicado en la isla sueca de Resaró, cerca de Estocolmo.

En las minas de Ytterby se han descubierto cuatro elementos, bautizados en nombre del lugar: el ytrio (Y), el iterbio (Yb), el terbio (Tb) y el erbio (Er).

Ningún otro lugar ha sido honrado tantas veces en la tabla periódica.

A la hora de elegir el nombre para un elemento químico, los investigadores no limitan su inspiración a la Tierra: hay elementos bautizados con el nombre de cuerpos celestes.

El caso más notable es el del elemento número dos de la tabla, descubierto en 1868 por el astrónomo francés Pierre Jules César Janssen cuando observaba el espectro solar.

Lo llamó con el nombre que los antiguos griegos le daban al Sol, Helio (He).

Fue el primero (y, hasta ahora, único) elemento descubierto en el espacio exterior antes que en la Tierra.

En 1803 se descubrieron el cerio (Ce) y el paladio (Pd).

Ambos recibieron sus nombres por dos asteroides, Ceres y Palas, observados por primera vez dos años antes.

El elemento 92, descubierto en 1789, fue llamado uranio (U) por el planeta Urano, descubierto en 1781.

Cuando, ya en el siglo XX, la tecnología nuclear produjo los elementos 93 y 94, se volvió a mirar al sistema solar y se los bautizó neptunio (Np) y plutonio (Pu), respectivamente. Cuando le llegó el turno al elemento número 95, no había más planetas y se lo llamó americio (Am).

DE LOS SIMBOLOS

Normalmente, los símbolos de los elementos químicos son sus respectivas iniciales: C para el carbono, O para el oxígeno y así con muchos otros.

A veces, se recurre al nombre del elemento en otro idioma, como la K para el potasio (del latín kalium) o la W para el tungsteno (del alemán wolfram).

Y, como hay más elementos en la naturaleza que letras en el alfabeto, en muchos casos se debe recurrir a las dos primeras letras del nombre, como Ca para el calcio o He para el helio.

Pero hay un elemento cuyo símbolo es especialmente críptico: el mercurio, de símbolo químico Hg. Este símbolo deriva del nombre que los antiguos griegos le daban al mercurio: hydrargyros.

La etimología de este nombre es muy sencilla.

Hydros significa agua y, en general, líquido.

Argyros, quiere decir plata. De modo que el hydragyros sería plata líquida.

Parece natural que cuando los antiguos vieron mercurio por primera vez les pareció estar ante una extraña forma de plata líquida.

La idea del mercurio como plata líquida aparece también en otras palabras y expresiones. Alfonso X, el Sabio escribió un elogio de España en el que dice que esa tierra es “rica de metales de plomo, de estanno, de argén vivo, de fierro”.

El “argén vivo” al que se refiere Alfonso X es el mercurio. España era el principal productor de mercurio durante la Edad Media.

La palabra inglesa quicksilver (plata rápida o movediza), que a nosotros nos recuerda una marca de ropa, es un antiguo nombre inglés para el mercurio.

Es evidente que, para los antiguos ingleses, el mercurio era tan vivo como movedizo.

pagina12.com.ar